COVID-19 the latest threat to safety of Rohingya refugees

https://arab.news/ndycg

Many countries around the Bay of Bengal and Malacca Strait have been very gracious and generous to Rohingya refugees fleeing the genocide in Myanmar in the past couple of years. The sacrifices made by Bangladesh in hosting more than 1 million refugees are already well advertised. Other Muslim-majority countries in the region, in particular Malaysia and Indonesia, have also been very kind — especially since they experienced relatively small numbers of incoming refugees, which they could cope with well.

But attitudes toward the Rohingya have been hardening in recent weeks, and for reasons over which the refugees have no control: The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the lockdowns that necessarily followed, and the economic hardships which subsequently ensued.

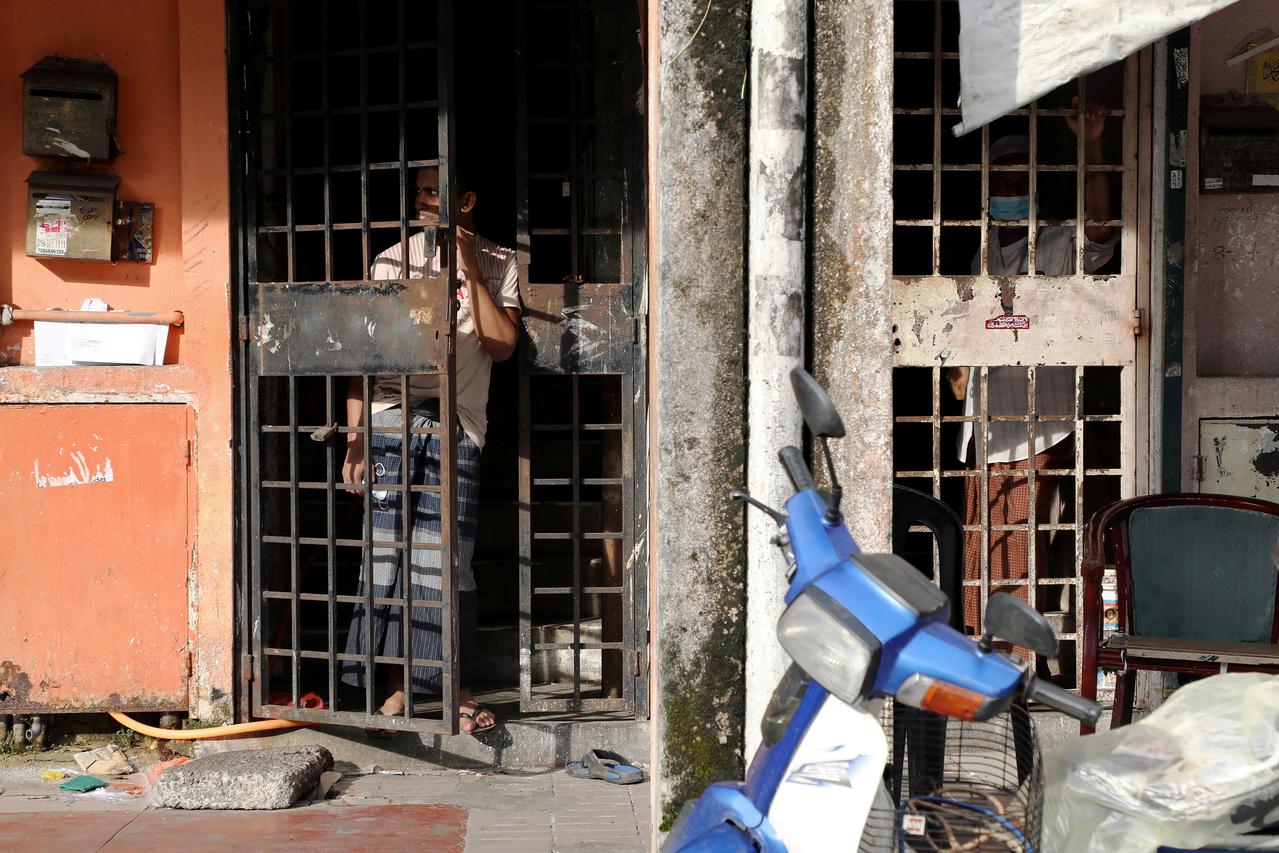

Malaysia has, unfortunately, made most of the news on this topic. It started with the Malaysian political leaders, including eventually the prime minister, saying that the country could not take any more refugees. But things started getting really ugly when it emerged authorities in one case were planning to expel a group of 269 Rohingya refugees back to sea after they had made landfall — in violation of international law — and depressingly petty when Rohingya child refugees were barred from attending kindergarten over cited fears of COVID-19 transmission risks.

To have seen attitudes turn so quickly, and so dramatically, in a country like Malaysia, which is generally regarded as one of the most open and liberally minded in the region, is both deeply sad and very alarming for the long-term prospects of the Rohingya.

It also highlights the urgent need for internationally agreed and enforced long-term solutions to the Rohingya situation, with a plan for them to become a self-sufficient and economically viable community in their own right, likely around Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh, where the largest number of Rohingya are already encamped in relative safety — for now.

One potential upside of this shift in attitude toward the Rohingya problem would be if the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries once again grew alive to their situation as it relates to the internal conduct of Myanmar (which is a member of ASEAN, unlike Bangladesh). They could use their leverage within the regional grouping to pressure Myanmar to ease off its continued assault against the 200,000 Rohingya who remain in the country, just as they did in the aftermath of the 2015 Southeast Asian migration crisis.

A level-headed response to renewed concerns over large flows of refugees against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic would be to focus on the original cause of the migration, which is to say the genocidal policies of the state and the military of Myanmar against the Rohingya in their native lands in the west of the country. At the very least, ASEAN members could impose sanctions and demand that Myanmar picks up the tab for the chaos and the costs caused by the refugees created by its internal conduct. And such a policy could become especially effective if it were done in cooperation with Bangladesh, the country most affected by the situation and most entitled to demand reparations from Myanmar over the fiscal costs of the refugee crisis.

A level-headed response to renewed concerns over large flows of refugees would be to focus on the original cause of the migration.

Dr. Azeem Ibrahim

It is quite difficult to see why regional players, and especially bodies like ASEAN, would not come together for this aim, especially as they are becoming more impatient with renewed waves of refugees. Myanmar has no leverage or standing in the matter, and it is a notoriously unreliable regional player. Supposedly, ASEAN partners might want to maintain good relations with Naypyidaw in the hope that such relations could bear economic and trade dividends, but Myanmar as a state has already proven itself no more reliable now, under the political leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi, than it had been under the old, isolationist military juntas. Letting them get away with causing this degree of chaos is not going to be economically beneficial to anyone in the long run.

It is thus time for the international community, not least the countries of the region, to come together and start imposing costs on Myanmar for the genocide against the Rohingya, as well as using some of the returns from such a policy to build a sustainable future for the Rohingya around Cox’s Bazar. This will stop the continuous outflow of refugees if that is the only thing these countries care about, but it is also both good and necessary to offer this people an assurance that they still have a future as a community.

- Dr. Azeem Ibrahim is a Director at the Center for Global Policy. Twitter: @AzeemIbrahim